Photo by Tim Marshall

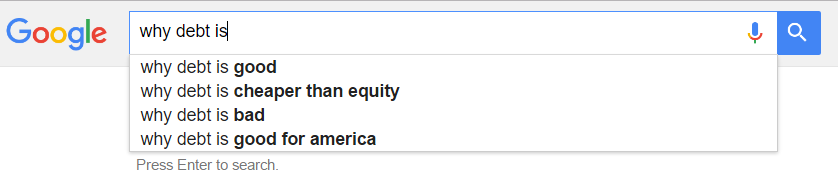

If you search google with “why debt is…” it will first complete your query with “why debt is good.”

I went down that rabbit hole to see the reasons people have for thinking (or rationalizing) that their debt is good. The idea of “Good Debt” versus “Bad Debt” is perpetuated throughout the internet. Good debt, as you may have heard from age-old wisdom, helps you buy things like houses and cars which require large capital investments but hold value and, in the case of houses, hopefully appreciate in value over time. Bad debt is when you go on weekly retail-therapy shopping sprees with your 17 credit cards and carry full balances at 24.99% interest while only paying the minimum due each month.

Good debt such as “mortgage, student and auto loan debt can help strengthen your financial position” (nerdwallet)

Let’s pump the brakes for a second and take a look at some mind-blowing statistics about debt in the United States. According to Nerd Wallet’s American Household Credit Card Debt Study, as of Quarter 1 in 2016:

The average credit card debt for a U.S. household is $15,310

The average mortgage debt for a U.S. household is $171,775

The average car loan debt for a U.S. household is $27,188

The average student loan debt for a U.S. household is $48,986

Keep in mind that household debt is generally defined as the amount of money that all adults in the household owe financial institutions. In 2015, the average American household consisted of 2.54 people. Acknowledging that children are included in the “American household” statistic, I’m going to make a wild guess and say that the average American household contains approximately 2 adults. So divide those debt statistics in half and you’re still looking at a whole lot of money per individual.

This study’s key findings were: “The rise in the cost of living has outpaced income growth over the past 12 years. While median household income has grown 26% since 2003, household expenses have outpaced it significantly — with medical costs growing by 51% and food and beverage prices increasing by 37% in that same span.”

A quick note here regarding mean (average) and median (middle-most) incomes. Mean income is the measure of the total combined income divided by the number of incomes combined. Median income is the amount that divides the range of incomes in half, with half of household incomes above and half of household incomes below that amount. Mean income can easily be skewed by few very large incomes, whereas median income is representative of the more “central” income. [Source] Alright, so now that we have that straight, I can give you more statistics (yay? yay!). Nerd Wallet reports “the average household is paying a total of $6,658 in interest per year. This is 9% of the average household income ($75,591) being spent on interest alone” and 10% of the median household income of $68,426 in 2014 (2014 figures used for consistency with the study’s numbers — the Census Bureau’s statistics are published using the previous year’s data).

Being in debt is very expensive.

Additionally, I was interested in their numbers regarding entreprenuers, since I plan to become one. I was shocked to learn that “households run by self-employed individuals spend $11,545 in interest annually, whereas heads of household working for someone else only pay $6,925 to finance their debt each year. In fact, self-employed people pay more in interest in every category considered, except for student loans.” That is 17% of the median income being used exclusively to pay interest on debts for self-employed individuals! With these facts in mind, it’s becoming exceedingly clear that being in debt is, in fact, a very expensive endeavor.

The narrative young people hear about debt is almost always from their parents and their educational institutions. Many parents, for example, believe that assuming debt in the form of a mortgage is acceptable, and in fact necessary, for the simple success in life of purchasing (rather, borrowing) a shelter to call home. Renting is often-times considered to be akin to throwing money away. After all, they could very well be mortgaging the home you grew up in. Your family will oftentimes also condone your decision to buy a new car through a car loan. Your school, below college level, may never teach personal finance. If it does, it is woefully inadequate at best, with lessons on budgeting and interest, but no deep dive into the effect that assuming massive debt as an 18 year old can have on your life for the next 21 years. Your university is likely to educate you about loans, but only in the intent of assisting you in taking out more. After all, it’s a bit too late to save much for college once you’re already enrolled in it, and they definitely want to keep you coming back with those big tuition checks each semester.

Back to our google search.. the occasional article in your “good debt” search will give you a new perspective: ‘Good’ debt is a myth.

“There is only better debt and worse debt. ” (U.S. News)

In my reality, no debt is good. Does it comfort me to know that the nearly $100,000 of student loan debt I had when I graduated college is considered “better debt?” Not at all. Would I feel secure in my home “ownership” if I was paying several hundred dollars a month in interest on the several hundred-of-thousands of dollars I owe on my home, because this debt is “helping” in the form of building positive credit history and potentially building wealth? Frankly, no.

With the scary statistics about American debt, it’s a wonder anyone can live debt free. Most people will accept debt as a way of life. I won’t accept that debt has to be part of my life, nor will I let my current debt dictate my path in life. Debt is the antithesis to the life I want to lead. Instead of a life of freedom, simplicity, location independence and passionate work and service; debt locks me down to a high-paying job in one location, increases my stress, and restricts my choices for many years in the future.

Once my decision to live debt-free was made, the plan to achieve my goal fell into place. Simple and two-fold, here’s the deal:

- Pay all current debts.

- Don’t assume any additional debts.

Simple doesn’t mean easy, but I’ve been making strides. In one year, I paid off $37,785, which is 40% of my student loan debt. I can tell you that, odd as it sounds, step 1 is easier than step 2. Paying my debts only requires the discipline to transfer money (albeit aggressively large amounts) towards those loans each month. Preventing any additional debt is harder, with the pressure from family and society to own the typical symbols of success, especially a house. My parents and friends are slowly coming around to my crazy, mortgage- and rent-dodging tiny house idea. More on that in my next post.

What do you think?

Is it really all that crazy and unattainable to be debt free? Is it something you’re personally aiming for?